Lavoro ben fatto is an expression meaning “work done well”. It was first explained to me as craftsmanship for its own sake, as putting time and effort into little details which only someone looking very closely can appreciate. For example, the way the seams of a garment have been sewn. It might not make a difference in how the garment looks on the rack, but that extra time and consideration matters to whoever sewed the garment (and, hopefully, to whoever wears it).

When I think of lavoro ben fatto, I often think of San Giuseppe (St. Joseph) as the patron saint of workers. One of his feasts is May 1–International Workers’ Day! San Giuseppe is prayed to in times of unemployment, and the celebration of his feasts in Italy explicitly emphasizes the necessity of charity and public welfare.

But it is important that we also recognize women’s labor, which is so often devalued. In fact, as women enter traditionally male-dominated fields, the average wages in those fields drop. Women’s labor is important, whether we are performing that labor in a traditionally male-dominated field, in a traditionally female-dominated field, or within the home.

In Salemi, Sicily, the labor of both men and women–of San Giuseppe and Maria Santissima–is celebrated as part of the feast of San Giuseppe on March 19. Men spend days setting up elaborate altars surrounded by greenery. Women spend days baking special breads shaped into sacred symbols. These symbols include the emblems of traditionally male and female labor: the breads baked to represent San Giuseppe are covered in carpenter’s tools, while the breads baked for Maria Santissima have the tools of weaving and sewing on them. These breads are so intricately detailed that they are famous throughout the region.

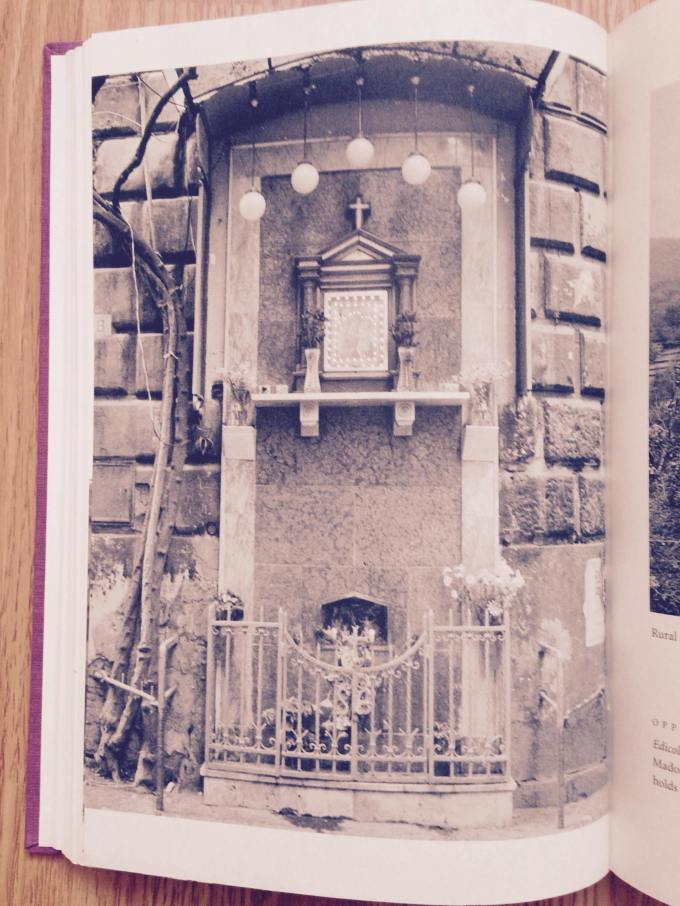

An altar for the feast of San Giuseppe in Salemi, Sicily. On the bottom left is a bread representing the madonna, in the bottom center is a bread representing Jesus, and on the bottom right is a bread representing St. Joseph.

I’ve been reflecting on lavoro ben fatto a lot recently, having just started a new job which is challenging me to pay particular attention to small details. So it was deeply inspiring to find Vincenzo Moretti’s Il Manifesto del Lavoro Ben Fatto, a manifesto about work done well and the rights of the people who do it. While reading through the manifesto (there’s even an English translation!), I’ve been thinking of the people of Salemi who work tirelessly for days every year out of pure devotion.

This intersection of devotion, justice, and excellence is truly inspiring to me. It’s something that I will always hope to manifest in my own lavoro, whether I’m taking on a new project at work, typing up a blog post, or just giving everything I’ve got in a barre class. And I hope you’ll join me in putting your whole heart into your lavoro next year, whatever kind of work you do.

Best wishes for 2017,

M.V.